Or try one of the following: 詹姆斯.com, adult swim, Afterdawn, Ajaxian, Andy Budd, Ask a Ninja, AtomEnabled.org, BBC News, BBC Arabic, BBC China, BBC Russia, Brent Simmons, Channel Frederator, CNN, Digg, Diggnation, Flickr, Google News, Google Video, Harvard Law, Hebrew Language, InfoWorld, iTunes, Japanese Language, Korean Language, mir.aculo.us, Movie Trailers, Newspond, Nick Bradbury, OK/Cancel, OS News, Phil Ringnalda, Photoshop Videocast, reddit, Romanian Language, Russian Language, Ryan Parman, Traditional Chinese Language, Technorati, Tim Bray, TUAW, TVgasm, UNEASYsilence, Web 2.0 Show, Windows Vista Blog, XKCD, Yahoo! News, You Tube, Zeldman

Amazon is linking site hiccups to AI efforts | InfoWorld

Technology insight for the enterpriseAmazon is linking site hiccups to AI efforts 11 Mar 2026, 1:18 am

Amazon reportedly convened an engineering meeting Tuesday to discuss “a spate of outages” that are tied to the use of AI tools, according to a report in the Financial Times.

“The online retail giant said there had been a ‘trend of incidents’ in recent months, characterized by a ‘high blast radius’ and ‘gen-AI assisted changes’” according to a briefing note for the mandatory meeting, the FT said. “Under ‘contributing factors,’ the note included ‘novel genAI usage for which best practices and safeguards are not yet fully established.’”

The story quoted Dave Treadwell, a senior vice-president in the Amazon engineering group, as saying in the note that “junior and mid-level engineers will now require more senior engineers to sign off any AI-assisted changes.”

However, said Chirag Mehta, principal analyst for Constellation Research, the senior engineer sign-off idea may inadvertently undo the key benefit of the AI strategy: efficiency.

“If every AI-assisted change now needs a senior engineer staring at diffs, the enterprise gives back much of the speed benefit it was chasing in the first place,” Mehta said. “The real fix is to move review upstream and make it machine-enforced: policy checks before deployment, stricter blast-radius controls for high-risk services, mandatory canarying, automatic rollback, and stronger provenance so teams always know which changes were AI-assisted, who approved them, and what production behavior changed afterward.”

The requirement for approvals follows several AI-related incidents that took down Amazon and AWS services, including a nearly six hour long Amazon site outage earlier this month, and a 13-hour interruption of an AWS service in December.

Glitches inevitable

Analysts and consultants said it is hardly surprising that enterprises such as Amazon are discovering that non-deterministic systems deployed at scale will create embarrassing problems. Humans in the loop is a fine approach, but there have to be enough humans to reasonably handle the massive scope of the deployment. In healthcare, for example, telling a human to approve 20,000 test results during an eight-hour shift is not putting meaningful controls in place. It is instead setting up the human to take the blame for the inevitable test errors.

Acceligence CIO Yuri Goryunov stressed that glitches like these were always inevitable.

“To me, these are normal growing pains and natural next steps as we’re introducing a newish technology into our established workflows. The benefits to productivity and quality are immediate and impressive,” Goryunov said. “Yet there are absolutely unknown quirks that need to be researched, understood and remediated. As long as productivity gains exceed the required remediation and validation work within the agreed upon parameters, we’ll be OK. If not, we’ll have to revert to legacy methods for that particular application.”

‘Reckless’ strategy

However, Nader Henein, a Gartner VP analyst, said that he expects the problem to get worse.

“These kinds of incident will continue to happen with more frequency. The fact is that most organizations think they can drop in AI-assisted capabilities in the same way that they can drop in a new employee, without changing the surrounding structure,” Henein said. “When we hand an AI system a task and a rulebook, we might think we’ve got things locked down. But the truth is, AI will do whatever it takes to achieve its goal within those rules, even if it means finding creative and sometimes alarming loopholes.

“It’s not that AI is malicious. It’s just that it doesn’t care. It doesn’t have the boundaries, the empathy, or the gut check that most people develop over time.”

In view of this, said Flavio Villanustre, CISO for the LexisNexis Risk Solutions Group, the typical enterprise AI strategy is “reckless.”

“You could consider the AI system as some sort of genius child with little and unpredictable sense for safety, and you give it access to do something that could cause significant harm on the promise of performance increase and/or cost reduction. This is close to the definition of recklessness,” Villanustre said.

“As a minimum, if you did this in a traditional manner, you would try this in a test environment independently, verify the results, and then migrate the actions to the production environment,” he noted. “Even though adding a human in the loop can slow things down and somewhat decrease the benefits of using AI, it is the correct way to apply this technology today.”

Other practical tactics

However, the human in the loop isn’t a complete solution. There are other practical tactics that help minimize AI exposure, said cybersecurity consultant Brian Levine, executive director of FormerGov.

“Traditional QA processes were never designed for systems that can generate novel errors no human has ever seen before. That’s why simply adding more human oversight doesn’t solve the problem. It just slows everything down while the underlying risk remains,” Levine said. “AI introduces a new category of failure: unknown‑unknowns at machine speed. These aren’t bugs in the traditional sense. They are emergent behaviors. You can’t patch your way out of that.”

Even worse, Levine argued, is that these bugs beget far more bugs.

“AI doesn’t just make mistakes. It makes mistakes that propagate instantly. Enterprises need a separate deployment pipeline for AI‑assisted changes, with stricter gating and automated rollback triggers,” he said. “If AI can write code, your systems need the equivalent of financial‑market circuit breakers to stop cascading failures. This means automated anomaly detection that halts deployments before customers feel the impact.”

He noted that the goal isn’t to watch AI more closely, it’s to give it “fewer ways to break things.” Techniques such as sandboxing, capability throttling, and guardrail‑first design are far more effective than trying to manually review every change.

Levine added: “AI can accelerate development, but your core infrastructure should always have a human‑authored fallback. This ensures resilience when AI‑generated changes behave unpredictably.”

Need a separate operating model

Manish Jain, a principal research director at Info-Tech Research Group, agreed. The Amazon situation is not as much evidence that AI makes more mistakes as it is evidence that AI now operates at a scale where even small errors can have “a massive blast radius” and may pose “an existential threat” to the organization.

“The danger isn’t that AI may make mistakes,” he said. “The danger is that it compresses the time humans have to intervene and correct a disastrous trajectory. With the advent of agentic AI, time‑to‑market has dropped exponentially. Governance, however, has not evolved to contain the risks created by this pace of technological acceleration.”

Jain stressed, however, that adding people into the mix is not, on its own, a fix. It has to be done reasonably, which means making an honest guess how much one human can oversee meaningfully.

“Putting a human in the loop sounds prudent, but it is not a panacea,” Jain said. “At scale, the loop soon spins faster than the human. Human in the loop cannot be the hammer for every agentic AI nail. It must be complemented by human‑over‑the‑loop controls, informed by factors such as autonomy, impact radius and irreversibility.”

Mehta added, “AI changes the shape of operational risk, not just the amount of it. These systems can produce code or change instructions that look plausible, pass superficial review, and still introduce unsafe assumptions in edge cases.

“That means companies need a separate operating model for AI-assisted production changes, especially in checkout, identity, payments, pricing, and other customer-critical paths. Those are exactly the kinds of workflows where the tolerance for experimentation should be extremely low.”

Claude Code adds code reviews 10 Mar 2026, 11:31 pm

Anthropic has introduced Code Review to Claude Code, a new feature that performs deep, multi-agent code reviews that catch bugs humans often miss, the company said.

Introduced March 9, Code Review is available in a research preview stage for Claude for Teams and Claude for Enterprises customers. Dispatching agents on a pull request, Code Review dispatches a team of agents that look for bugs in parallel, verify bugs to filter out false positives, and rank bugs by severity, according to Anthropic. The result appears in the pull request as a single, high-signal overview comment, plus in-line comments for specific bugs. The average review takes around 20 minutes, Anthropic said.

Anthropic has been running Code Review internally for months. On large pull requests (more than 1,000 lines changed), 84% get findings, averaging 7.5 issues. On small pull requests of fewer than 50 lines, the rate of findings drops to 31%, averaging 0.5 issues. Anthropic has found that its engineers mostly agree with what Code Review surfaces, marking less than 1% of findings as incorrect.

TypeScript 6.0 reaches release candidate stage 10 Mar 2026, 9:03 pm

TypeScript 6.0, a planned update to Microsoft’s strongly typed JavaScript variant, has reached the release candidate (RC) stage, with the RC adding type checking for function expressions in generic calls.

The last TypeScript release based on the JavaScript codebase, before TypeScript 7.0 introduces a compiler and language service based on the Go language for better performance, TypeScript 6.0 reached the RC stage on March 6. General availability of the production release has been set for March 17, although the RC was supposed to be released February 24, meaning it was 10 days late. The TypeScript 6.0 RC, which follows the February 11 beta release, can be installed via NPM by running the command npm install -D typescript@rc.

New in the RC is an adjustment in type checking for function expressions in generic calls, especially those occurring in generic JSX expressions, according to Microsoft. Aimed at aligning TypeScript 6.0 with the planned behavior of Go-based TypeScript 7.0, this adjustment will typically catch more bugs in existing code, though developers may find that some generic calls may need an explicit type argument.

Also, Microsoft has extended its deprecation of import assertion syntax (i.e. import ... assert {...}) to import() calls like import(..., { assert: {...}}). And DOM types have been updated to reflect the latest web standards, including some adjustments to Temporal APIs.

Other changes in TypeScript 6.0 include the RegExp.escape function for escaping regular expression characters such as *, ?, and +. Based on an ECMAScript proposal that has reached stage 4, RegExp.escape is now available in the es2025 library. Also, the contents of lib.dom.iterable.d.ts and lib.dom.asynciterable.d.ts are now included in lib.dom.d.ts. TypeScript’s lib option lets developers specify which global declarations a target runtime has.

Now feature-complete, TypeScript 6.0 also deprecates the asserts syntax. The asserts keyword was proposed to the JavaScript language via the import assertions proposal; however, the proposal eventually morphed into the import attributes proposal, which uses the with keyword instead of asserts.

Microsoft expects TypeScript 7.0 to follow soon after TypeScript 6.0, with the goal of maintaining continuity while enabling a faster feedback loop for migration issues discovered during adoption.

JetBrains launches Air and Junie CLI for AI-assisted development 10 Mar 2026, 3:18 pm

JetBrains has introduced two new tools for AI-assisted software development: Air, an environment for delegating coding tasks to multiple AI agents and running them concurrently, and Junie CLI, an LLM-agnostic coding agent.

Both were announced on March 9. Air, in public preview, can be downloaded from air.dev, while Junie CLI, in beta, is accessible at junie.jetbrains.com.

Air, now free for MacOS with Linux and Windows versions coming soon, is an agentic development environment, or ADE, built on the idea of integrating the essential tools for managing coding agents into a single coherent experience, JetBrains said. Serving as a single workspace where Claude Agent, Gemini CLI, Codex, and Junie CLI can work side-by-side, Air helps developers navigate a codebase and easily switch back and forth between different coding agents. Developers can mention a specific line, commit, class, method, or other symbol when defining a task, providing the agent with precise context instead of a blob of pasted text. And when the task is done, Air displays the changes in the context of the entire codebase, along with essential tools like a terminal, Git, and a built-in preview, according to JetBrains. Air will soon add support for additional coding agents via the Agent Client Protocol (ACP) through the ACP Agent Registry, the company noted.

Like Air, Junie CLI is built to ensure that code generated by agents is grounded in the reality of the codebase. The standalone coding agent is designed to be LLM-agnostic and open to all high-performing models, capable of solving complex problems, context-aware by default, and reliable and secure, JetBrains said. With the planned March release, Junie CLI will support use directly from the terminal, inside any IDE, in CI/CD, and on GitHub or GitLab. Junie CLI currently supports top-performing models from OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Grok, and will be integrating the latest models as they are released.

MariaDB taps GridGain to keep pace with AI-driven data demands 10 Mar 2026, 9:59 am

MariaDB, the company behind the open-source fork of MySQL, is planning to acquire in-memory computing middleware provider GridGain to bolster its platform for high-performance data and artificial intelligence (AI) workloads.

The database provider is planning to infuse its relational database with the California-headquartered startup’s in-memory technology, which it says will enable its database offerings to be ready for real-time and AI workloads that demand sub-millisecond latency.

Analysts, too, see potential in the acquisition.

“This acquisition is about closing a performance gap. Putting these two together has the potential to reduce the time it takes to access and process operational data,” said Robert Kramer, principal analyst at Moor Insights and Strategy.

“That matters for modern applications where systems need to react immediately to business events. Consider fraud detection, dynamic pricing, operational monitoring, or automated workflows that depend on fast decisions,” Kramer added.

GridGain’s recent addition of support for AI workloads through functionalities, such as in-memory machine learning and vector search, will enable MariaDB to address the emerging requirement for real-time AI inferencing to support generative and agentic AI workloads, said ISG’s director of software research Matt Aslett.

Further, Aslett said that GridGain’s ability to accelerate performance and scalability while maintaining transactional integrity and durability will enable MariaDB to expand to “important” industry sectors, such as financial services and telecommunications.

In fact, Aslett sees the acquisition as an indication of MariaDB’s improved stability following its acquisition by K1 Investment Management, after going through a difficult financial phase.

Under K1’s stewardship, the database provider recently reacquired SkySQL and later lapped up Codership to add active-active synchronous replication capabilities to its database offerings.

However, analysts cautioned that while the acquisition marks a step in the right direction in MariaDB’s comeback efforts and could help it re-enter conversations with CIOs, it is unlikely to suddenly transform the company’s platform into the centerpiece of enterprise AI stacks.

“The real test will be execution. Integrating two complex technologies and presenting them as a cohesive platform is not trivial. Customers will want to see that the capabilities work smoothly together and that the company can deliver a consistent roadmap around the combined technology,” Kramer said.

Further, Kramer noted that MariaDB faces stiff competition as the market is already crowded with vendors that provide very deep ecosystems around data.

“Hyperscalers and major data platform vendors offer integrated services across storage, analytics, and model infrastructure. MariaDB’s differentiation will likely depend on whether the combined platform can deliver operational speed and simplicity that organizations find easier to run than those larger stacks,” Kramer said.

When asked about how the acquisition will affect GridGain’s existing customers, the company, in a statement, said that nothing will change in the short term and current contracts, support teams, and technology remain “exactly as they are today”.

In the long-term, though, MariaDB hinted that GridGain customers might have to buy a single integrated product: “Long-term, customers will gain the added benefit of a converged platform that combines MariaDB’s relational reliability with GridGain’s sub-millisecond speed — providing a single, high-velocity foundation for the next generation of AI and enterprise workloads.”

Neoclouds run AI cheaper and better 10 Mar 2026, 9:00 am

Enterprises are under intense pressure to deliver AI outcomes that are visible, measurable, and repeatable without blowing up their cloud budgets. That’s why neoclouds have arrived at exactly the right moment. By neoclouds, I’m referring to GPU-centric, purpose-built cloud services that focus primarily on AI training and inference rather than on the sprawling catalog of general-purpose services that hyperscalers offer.

In many cases, these platforms deliver better price-performance for AI workloads because they’re engineered for specific goals: keeping expensive accelerators highly utilized, minimizing platform overhead, and providing a clean path from model development to deployment. When a provider’s entire business is built around GPU throughput, interconnect, scheduling, and serving efficiency, the result is often a more direct and cost-effective experience than forcing every AI workload into a general-purpose environment.

But here’s the reality check: Cheaper GPUs don’t automatically translate into cheaper AI, and better AI isn’t just about faster training runs. The real cost—financial and organizational—shows up when you try to operationalize these environments at scale across teams, products, and regulatory boundaries. That’s where neoclouds can either become a strategic advantage or yet another expensive science project.

Another cloud in the mix

Most large enterprises already face a messy, unavoidable truth: they’re not multicloud because it’s fashionable; they’re multicloud because the business is multi-everything. Different regions, mergers and acquisitions, data residency rules, legacy contracts, preferred vendors, and specialized services pull you into a world where you’re using a surprising number of cloud providers. It’s not unusual to see enterprises interacting with a dozen or more hyperscalers, SaaS platforms, and niche providers once you add everything up.

In that context, a neocloud is not a sidecar. It is one more cloud that must be operated, maintained, secured, and governed. It introduces new identity and access patterns, network topologies, logging and monitoring surfaces, key management decisions, and incident response runbooks. You don’t just try it for AI. You absorb it into the enterprise operating model whether you plan to or not.

The most common failure pattern I see is when enterprises adopt a neocloud for a pilot, achieve impressive benchmark results, and then quietly create a silo. A silo of specialized talent. A silo of bespoke operational procedures. A silo of that one team that knows how to deploy and secure the environment. It works until it doesn’t. Then scale collapses under the weight of confusion, inconsistent controls, and an inability to extend the platform across multiple lines of business.

Neoclouds don’t erase complexity

Neoclouds win because they remove distractions. They’re often designed to do a smaller number of things extremely well: provision GPU capacity quickly, optimize scheduling, support modern AI frameworks, and offer efficient inference endpoints. That focus matters. It can mean faster time to capacity, better utilization, and fewer mystery costs from overprovisioned infrastructure or general-purpose service sprawl.

However, enterprise AI is never just training and inference. The AI life cycle touches data pipelines, governance, model risk management, privacy controls, observability, software supply chain security, and cost allocation. Even when the neocloud handles the GPU part beautifully, the surrounding system still needs to be integrated. That integration is where many organizations stumble.

If you treat a neocloud like a standalone island, you create two competing realities: the enterprise’s standard cloud operating approach on one side and the neocloud’s special AI way of doing things on the other. People will route around controls to speed up. Logs won’t land where security teams can see them. Identity will drift. Secrets will multiply. Costs will be hard to attribute. When something breaks at 2 a.m., you’ll discover that your normal operations team can’t help because the neocloud is owned by a small expert group that’s now the bottleneck for the entire company.

Create an operating model first

The first step to leveraging a neocloud is to avoid signing a contract or migrating a notebook. The first step is deciding how you will handle the additional multicloud complexity without slowing the business or weakening your security posture.

That means establishing common security layers, common governance layers, and common operations layers that span all cloud providers you use, including the neocloud. Common does not mean identical implementations everywhere; it means consistent outcomes and controls: unified identity patterns, consistent policy enforcement, centralized logging, standardized vulnerability management, and repeatable deployment practices that don’t vary wildly depending on which cloud you’re in.

If your enterprise is already juggling many providers, a neocloud should be integrated into the same systemic approach. If you don’t have that approach, adopting a neocloud will force you to build it, either intentionally and cleanly or accidentally and painfully.

Before you adopt a neocloud

The first consideration is whether you can extend your security and governance controls to the neocloud without creating exceptions. If your identity strategy, policy as code, encryption standards, logging pipelines, and audit workflows can’t reach this environment, you’re not adopting a GPU platform—you’re adopting a compliance problem that will grow with every model you deploy.

The second consideration is whether you have a realistic plan for multicloud operations at scale, including provisioning, observability, incident response, and change management. Neoclouds tend to move fast, and AI teams tend to move even faster; if your operational layer can’t keep up with the velocity of model iteration and deployment, you’ll either throttle innovation or allow unsafe practices to become the default.

The third consideration is how you will manage cost, capacity, and workload placement across an expanded provider landscape. The value of neoclouds often depends on utilization and correct workload fit; without clear chargeback or showback, scheduling discipline, and placement rules, you’ll end up with fragmented spend, stranded GPU capacity, and architecture decisions driven by convenience rather than economics.

Neoclouds are part of the system

Neoclouds are not a fad, and they’re not merely a cheaper place to run the same workloads. They represent a specialization trend in cloud computing: platforms optimized for a narrow, high-value domain. For AI training and inference, that specialization can absolutely translate into better economics and better performance.

But the enterprise buys outcomes, not benchmarks—secure, governable, and operable outcomes that scale across teams and product lines. If you don’t treat neoclouds as systemic infrastructure, you’ll recreate the same mistakes we made in the early days of cloud: fragmented tools, inconsistent security, and hero-driven operations that collapse when the heroes leave.

Should you adopt neoclouds? Yes. Use them to drive down unit costs and increase AI throughput. Just don’t pretend they’re separate from the rest of your multicloud reality. The moment you run production workloads, they become part of the enterprise. If you plan for that moment from day one, neoclouds can become the accelerator your AI program needs—without accelerating your risk.

How developers can bring voice AI into telephony applications 10 Mar 2026, 9:00 am

In the era of support apps and chatbots, telephony continues to hold strong as the backbone of customer communication, and voice AI is entering the call center scene to further streamline customer interaction.

However, this means developers are suddenly being confronted with a whole new set of challenges, foremost among them the difficulty of bridging the gap between layers of AI and “legacy” telecom networks. In fact, as large language models constantly evolve and update, the voice AI pipeline must be designed from the outset for easy switching. With much uncertainty surrounding the shift, one thing is clear: It’s crucial not to underestimate the challenges latent in AI-telephony integration.

Voice AI agents have a multitude of enterprise use cases. They are a valuable tool for setting customer appointments, then rescheduling and canceling them as needed. Moreover, they serve to triage inbound calls, before routing them correctly to human agents. Voice AI can even shoulder the responsibility of organizing ETAs, coordinating deliveries, and scheduling candidates for interviews.

Businesses should assume from the start that they will want to change components of the voice AI pipeline and pick accordingly, focusing on systems that give them flexibility. That said, further problems are continuing to present themselves to developers.

Why telephony is still hard for developers

People often assume that a voice AI agent is simply ChatGPT with a voice, an agent embedded in AI that is receiving and routing calls. This is far from reality. Voice AI agents require a whole infrastructure, containing multiple components that flesh out the LLM to operate successfully in the real world.

- Large language models (LLMs): The cornerstone of any AI call system, they interpret intent, plan steps, and generate responses, all of which enable seamless comms between caller and agent.

- Speech-to-text (STT): This technology is the crucial channel of the system as it converts caller audio to text, without which analytics cannot take place.

- Text-to-speech (TTS): The counterpart and inverse of STT, synthesizing the agent’s response and making it sound like natural speech.

- Turn-taking: How to remain conversational when relying on an AI? That’s where turn-taking comes into play, with voice activity detection and barge-in policies that allow the tone to stay natural.

- Telephony gateway: This bridging device converts PSTN/SIP/WebRTC and manages signaling and media.

These pieces fit together in a complex network of telephony infrastructure, albeit one with some limitations. Local telecom carriers must reckon with these, in addition to their business’s own compliance needs, requirements, and constraints. To this end, communications networks always comprise a mix of vendors and technologies, meaning that enterprises need to stay flexible as they integrate new components with existing elements.

This is especially true for voice AI applications, which have some of the most stringent technical requirements. Application developers should aim to coordinate voice AI-specific elements while interoperating with existing systems.

The technical reality check

Developers face a set of gritty technical problems when integrating voice AI into telecom networks. Moving forward with building a voice AI agent—one that really works in production—means unpacking these issues and building solid solutions.

Managing latency

Latency is a niggling issue that threatens any good voice AI system. Gaps and pauses before hearing a response are a red flag for callers: The user may conclude that the agent either isn’t there or that the tech isn’t working properly.

The International Telecommunications Union (ITU) recommends a mouth-to-ear latency of less than 400 milliseconds to maintain a natural conversation. “Mouth-to-ear” refers to the length of time between words leaving someone’s lips and hitting the ear, or being heard by the listener. It then usually takes humans a couple of hundred milliseconds to start to respond. All of this means that, in order to mimic human interaction, AI systems must be able to provide a response in a tight time window. The AI’s response will initiate another trip as the sound moves back through the network, allowing the original talker to hear the response. All in all, the whole interaction needs to take around a second, otherwise it will start to feel off. In reality, most voice AI systems are on the cusp of reaching this measure, yet this is improving with new technologies and better techniques.

Latency can make or break effective real-time AI systems. We’ve seen this with cases of latency coupled with missing language support in health care. A startup based in Australia, for example, wanted to use an AI caller to check on elderly Cantonese-speaking patients. This would seem to be a good use of the technology. However, high latencies to US-based voice AI infrastructure, plus a lack of Cantonese TTS, made the experience unnatural.

Solutions to latency problems resemble engineering modifications. You strive to cut latency wherever you can in the development phase. This requires real-time flows, end-to-end—that is, stream in and out concurrently, rather than waiting for the LLM to produce the full text output before passing it to the TTS to be synthesized.

Keeping a close eye on long delays during calls is also key. This allows a response to be injected when necessary, keeping pauses or silences to a minimum. In fact, another aspect of the solution is holding a steady stream of communication with the user. Rather than the line going silent, leading them to suspect something is wrong, it’s key to make a point to inform callers that a delay is coming up. Background noises can similarly instill confidence that your query is being handled despite any pauses.

Impersonal AI

Another problem for voice AI lies in the potential for AI to become quite monotonous and impersonal, leaving callers with the feeling they were dialed through to some homogenous AI system. Third-party TTS systems exist for this very purpose. Expanding voice options, bringing more variety to the service, help to retain a human touch.

It’s a mark of the diversity of the field that solutions in voice AI-telephony take many forms. Streaming TTS can allow for lower latency, while some vendors offer a wide variety of voices, allowing you to pick one that is unique to your business and needs. Some companies will already have a voice that is identifiable with their brand, meaning that they can clone and input that voice to their voice AI system. Having a distinctive voice speak directly to customers through telephony can be a powerful asset. Others, however, should be able to select from a variety of different voices to find one that aligns well with their brand.

Integrating with telephony systems

One further issue is integrating your AI agent with existing telephony systems, particularly the contact center and enterprise infrastructure. These are themselves often made up of a blend of systems from a mix of vendors; whilst the SIP standard governs most of traditional telephony, that is not a guarantee of interoperability. Indeed, older systems are often fixed or limited in their settings, meaning that new systems must be highly adaptable.

In this context, it makes sense to pick an experienced vendor, someone who knows how to interoperate in a variety of environments and with different systems. Another hack is to ensure they have solid debugging tools and the support needed to work through any unexpected issues that might crop up.

Network quality can vary wildly between countries, particularly in rapidly evolving regions like Latin America. For example, we have seen unreliable SIP interconnections from Mexico, with customers forced to route through the US, adding unnecessary latency. In turn, major investments in Brazil’s infrastructure in recent years have improved service not only within the country but also across the larger region. Ideally, your CPaaS (communications platform as a service) provider will have carrier relationships across many countries, allowing them to optimize traffic in all situations.

Five tips for building real-time voice AI that works

So, to summarize the above, I’ve pulled together five tips on how to build a real-time voice AI that actually works.

- Start by defining the needs and constraints of the user. It’s equally critical to be aware of latency tolerance, supported languages and geographies, as well as other factors like KPIs and compliance scope.

- Choose your comms integration and media path carefully. Specifically, think about where you stand in terms of voice versus messaging. If you go down the voice road, figure out what your architecture will look like, particularly around CPaaS, trunks, transfers, and DTMF (dual tone multi-frequency) signaling.

- No voice AI is complete without a solid, compatible real-time AI pipeline. First, pick an LLM; choosing the underlying LLM will power the behaviors of your voice system, influencing latency, compliance, tone, and much more. Having clarity on voice and pipelines from the start will help businesses craft an effective voice AI.

- Deep integration with existing systems is another piece of the puzzle, allowing the tech to disseminate important information and context about the caller, such as names and account details. Unnatural memory omissions from the bot are a serious non-starter. A well-integrated system can help avoid common downfalls (latency, missing barge-in, or hallucinations) and make your voice AI feel alive.

- Productionization is mission-critical to all telephony applications. It’s key to call centers, to real-time gaming and trading systems, and to your voice agent, which you’ve so successfully built with the goal of running flawlessly on every phone call. Properly built infrastructure enables the bot to manage word error rate, latency, and autoscaling.

Voice AI agents are constantly evolving, representing an iterative tech with a unique set of challenges. I’ll conclude with some tips for future-proofing your voice AI and telecom stack against this backdrop of evolution.

What’s next for real-time voice AI

One key piece of advice is to get ahead of the curve on LLM and speech vendors. Assume that these aren’t static components, but that you’ll want to swap them in order to move with the times. Don’t put yourself on the back foot, but make sure it’s possible to mix and match on your platform.

More broadly, avoid being caught out by evolutions in the tech. By anticipating quality and performance improvements in speech and AI, rather than being overtaken by them, you’ll be able to quickly mobilize improvements when they emerge. Even if you’re reaping the benefits of a certain approach today, don’t hold on for too long, or else a better strategy that’s coming out tomorrow will pass you by.

It’s also worth mentioning that the global reach of voice AI is both a challenge and an advantage. In the San Francisco Bay Area, a significant portion of voice AI orchestration platforms primarily target US users. That’s all well and good, but companies with more internationalized customer bases have the upper hand because they face challenges that many more localized companies have not yet experienced.

For example, latency is a major challenge internationally, where voice AI data centers may be further away (or only based in the US) and telecom carriers may be less reliable. This gives international providers the edge because their global footprint leads to solid carrier relationships and extensive voice AI partners.

Ultimately, it will only be a matter of years before the new generation of voice applications is much-improved over what we see today. In fact, the integration may be so seamless that it will be hard to tell the difference between AI agents and human agents in state-of-the-art systems. This should accelerate call centers in replacing their legacy IVR (interactive voice response) systems with voice AI. So too should it drive developers and stakeholders to build AI-driven call workflows fit for real-world use.

—

New Tech Forum provides a venue for technology leaders—including vendors and other outside contributors—to explore and discuss emerging enterprise technology in unprecedented depth and breadth. The selection is subjective, based on our pick of the technologies we believe to be important and of greatest interest to InfoWorld readers. InfoWorld does not accept marketing collateral for publication and reserves the right to edit all contributed content. Send all inquiries to doug_dineley@foundryco.com.

5 requirements for using MCP servers to connect AI agents 10 Mar 2026, 9:00 am

One of the most poweful collaborations between AI and tech giants, Model Context Protocol (MCP) is a standard for connecting AI agents. We need standards like MCP to orchestrate communication between AI agents, AI assistants, LLMs, and other resources. Such standards are also critical for developing more complex agentic workflows.

The MCP protocol enables two key technologies: The MCP server connects AI agents, makes them discoverable, and provides other operational services. The MCP gateway is a reverse proxy that serves as an interface between AI agents, MCP servers, and other services that support the MCP protocol.

Many organizations are utilizing AI agents from top-tier SaaS and security companies while also experimenting with ones from growing startups. Devops teams aim to build trustworthy AI agents while avoiding the risks of rapid deployment. The AI development roadmap will likely require agent-to-agent communication with the help of MCP servers.

Below are five requirements to consider before deploying an MCP server or connecting your AI agents to one.

Requirements for MCP servers

While MCP servers share similarities with other integration technologies, they also have key differences. MCP servers act as a catalog of tools and data for AI agents to use when responding to a prompt or completing a task. They centralize authentication, schemas, error handling, and streaming semantics for processing partial responses. Operational and security teams use MCP servers to monitor activity and respond to security incidents and AI agent performance issues.

The scope and scale of services orchestrated by MCP means teams must define their requirements inside a well-defined IT governance model.

“When using MCP to provide your agents with more tools to get their jobs done, make sure your governance requirements extend to that service,” says Michael Berthold, CEO of KNIME. “Before pointing your agent to an external MCP server, make sure you know and understand how prompts and data are processed, and potentially shared or used for other purposes. Don’t assume a tool that seems to be doing something in isolation isn’t using another AI underneath the hood.”

Also see: Five MCP servers to rule the cloud.

1. Define the MCP server’s scope

MCP servers can play a contextual role in agent-to-agent orchestrations. When an AI agent seeks other AI agents to complete a job, it can query an MCP server to identify potential resources and decide which to interface with. Defining the server’s scope helps shape its problem domain and ownership, as well as its governance, security, and other operational boundaries.

“Design your MCP servers to be narrowly focused, exposing specific and granular tools to your AI agents, instead of trying to be a general-purpose API,” says Simon Margolis, associate CTO of AI and ML at SADA, an Insights Company. “This makes it easier for the AI’s reasoning engine to discover the right tool dynamically and improves the reliability of the actions it takes. An MCP server acts as a smart adapter, translating the AI’s request into the exact command the underlying tool understands.”

“We’ve found that simple, explicit instructions, such as telling the model how to use a vendor’s command-line utility, can outperform a poorly integrated MCP server,” adds Andrew Filev, CEO and founder of Zencoder. “Overloading the model’s context with too many MCP tools can actually degrade performance, confuse the agent, and obscure reasoning paths.”

Creating separate servers for finance, HR, customer support, and IT simplifies creating access rules, monitoring operations for anomalies, and defining lifecycle management policies.

2. Establish integration governance

There are different schools of thought over what resources to connect through an MCP server. For example:

- Gloria Ramchandani, SVP of product at Copado, advises teams to pull data, settings, and context from the MCP server rather than keeping their own copies. “Using the MCP as the single place your agents rely on keeps everything consistent, reduces mistakes, and makes automation smoother as your teams grow,” Ramchandani said.

- James Urquhart, field CTO and developer evangelist at Kamiwaza, recommends against relying on MCP servers for data retrieval. “RAG approaches to incorporating live data into response generation still enable better security and performance than MCP integration.”

- Tun Shwe, AI lead at Lenses, says, “Don’t expose existing web and mobile APIs directly as MCP tools. Whilst it’s a quick way to get started, these APIs tend to be fine-grained with verbose responses; characteristics that are undesirable to AI agents, since they inflate token consumption.”

- Rahul Pradhan, VP of product and strategy of AI and data at Couchbase, advises against treating MCP-connected agents with access to a database as generic, low-risk APIs. He suggests the following instead:

- Treat every tool that can read or write data as highly privileged: Enforce least-privilege roles, segregate access by data sensitivity, and separate read from write paths.

- Design prompts so agents first invoke schema introspection tools to understand scopes, collections, and fields before issuing any operations.

- Constrain agents to vetted, parameterized queries or stored procedures, and log all calls, to reduce the risk of exfiltration, corruption, and compliance failures.

3. Implement security non-negotiables

Many organizations created AI governance policies when they rolled out LLMs, then updated them for AI agents. Deploying MCP servers requires layering on new security non-negotiables related to configuration, deployment, and monitoring.

“Prioritize security because tools exposed by an MCP server can change and may not have the same level of data security an agent expects,” says Ian Beaver, chief data scientist at Verint. “Prompt injection risks exist in both tool responses and user inputs, making tool use the primary vulnerability point for otherwise static foundation models. Therefore, treat all tool use as untrusted sources: Log every tool’s input and output to enable full auditability of agent interactions.”

One critical place to start is defining identity, authentication, and authorization for AI agents. Because AI agents will be discoverable through MCP servers, make sure to be clear and transparent on the scope and entitlements of their capabilities.

“Don’t give AI agents unrestricted access when connecting through MCP,” says Meir Wahnon, co-founder at Descope. “Even though MCP standardizes integrations, many servers still lack proper authentication or use overly broad permissions, leaving systems exposed. Apply the principle of least privilege: Grant narrow scopes, require explicit user consent, and keep humans in the loop for sensitive actions.”

Other security recommendations include isolating high-risk capabilities within dedicated MCP servers or namespaces and implementing cryptographic server verification. Key principles of MCP server security governance include secure communications, data integrity assurance, and incident response integration.

Three more security recommendations:

- Vrajesh Bhavsar, CEO and co-founder of Operant AI, says, “Don’t rely on traditional security approaches that depend on static rules and predefined attack patterns—they cannot keep up with the dynamic, autonomous nature of MCP-connected systems.”

- Arash Nourian, global head of AI at Postman, adds, “Don’t treat MCP as secure out of the box because it currently has close to zero built-in security, with no standardized authentication, weak session management, and unvetted tool registries that open the door to MCP-specific attacks like prompt or tool poisoning.”

- Or Vardi, technical lead at Apiiro, adds, “Keep humans in the loop for any sensitive or business-critical tasks, and also monitor and audit MCP activity to detect misuse early.”

4. Don’t delegate data responsibilities to MCP servers

Several experts cautioned that while MCP servers provide connectivity, they do not vet the data passing through them.

“Don’t assume MCP solves your underlying data quality problems,” says Sonny Patel, chief product and technology officer at Socotra. “MCP provides the connectivity layer, but AI agents can only be as effective as the data they access. If your systems contain incomplete, inconsistent, or siloed information, even perfectly connected agents will produce unreliable results.”

Developers should also scrutinize prompts and other inputs sent to their AI agents via MCP servers and make no assumptions about upstream validation.

“Always implement runtime interception to validate MCP inputs before they reach your agent’s reasoning engine, says Matthew Barker, head of AI research and development at Trustwise. “Attackers can poison tool descriptions, API responses, or shared context with hidden commands that hijack agent behavior. It only takes one compromised agent to cascade malicious instructions across your entire AI ecosystem through inter-agent communication.”

Pranava Adduri, CTO and co-founder, Bedrock Data, says, “Don’t connect AI agents to data sources via MCP without first classifying data and establishing access boundaries. MCP simplifies context sharing but can amplify risk if agents query sensitive or unverified sources.”

5. Manage the end-to-end agent experience

As organizations deploy more AI agents and configure MCP servers, experts suggest setting principles around end-user and operational experiences. Devops teams and SREs will want to ensure they have observability and monitoring tools in place to alert on issues and aid in diagnosing them.

Or Oxenberg, senior full-stack data scientist at Lasso Security, says to establish comprehensive observability with trusted MCP servers. “If you’re using an MCP gateway, remember it monitors only traffic going in and out of the MCP server. For full visibility, capture every interaction and user input, map and monitor the agent’s planning and actions, and track their tasks and decisions. Without this foundation, you can’t detect when agents drift from intended behavior or trace back security incidents.”

Developers should also limit an AI agent’s access to MCP servers and AI agents, granting access to only those providing relevant services. Broadening their access can lead to erroneous results and higher costs.

“As an integrator, you are now crafting a product experience for the agent persona and should treat the modulated toolkit with the same product discipline you apply to the developer UX: clarity, alignment, and value,” says Edgar Kussberg, group product manager of AI at Sonar. “When agents are given broad or generic MCP tools, they spend too much time and tokens exploring, filtering, reasoning, and failing to provide value, wasting budget, complicating review workflows, and diluting trust in agent outputs.”

As more organizations deploy AI agents into production, I expect a growing need to configure MCP servers to support agent-to-agent communication. Establishing an upfront strategy, nonfunctional requirements, and security non-negotiables should guide smarter and safer deployments.

Ruby sinking in popularity, buried by Python – Tiobe 9 Mar 2026, 9:57 pm

The Ruby language has been around since 1995 and still gets regular releases. But the language has dropped to 30th place in this month’s Tiobe index of language popularity, with Python cited as a reason for Ruby’s drop.

Ruby was the Tiobe language of the year in 2006, having displayed the highest growth rate in popularity that year, it is now close to dropping out of the top 30, according to Tiobe CEO Paul Jansen. Ruby’s March rating is .55%; the language was ranked 25th last month. “The main reason for Ruby’s drop is Python’s popularity. There is no need for Ruby anymore,” Jansen said. Ruby’s highest position was an eighth place ranking in May 2016.

Also in this month’s index, SQL, with a rating of 2%, and R, with a rating of 1.88%, swapped places in the top 10, with SQL now ranking eighth and R ninth. In addition, Swift re-entered the top 20 with a rating of 1.04%, while Kotlin fell to 22nd with a rating of .82%. And Google’s Dart language, once positioned as a rival to JavaScript, is on a path to sneaking back into the top 20. Dart ranked 25th this month with a rating of .69%.

The Tiobe Programming Community Index gauges language popularity based on a formula that assesses the number of skilled engineers worldwide, courses, and third-party vendors pertinent to a language. Popular websites such as Google, Amazon, Bing, Wikipedia, and more than 20 others are used to calculate the ratings.

In the bulletin accompanying this month’s index, Jansen addressed inquiries about switching from search engines to large language models (LLMs) to formulate the ratings. “The answer is no,” Jansen said. “The Tiobe index measures how many internet pages exist for a particular programming language. LLMs ultimately rely on the same sources—they are trained on and analyze these very same web pages. Therefore, in essence, there is no real difference.”

The Tiobe index top 10 for March 2025:

- Python, 21.25%

- C, 11.55%

- C++, 8.18%

- Java, 7.99%

- C#, 6.36%

- JavaScript, 3.45%

- Visual Basic, 2.5%

- SQL, 2%

- R, 1.88%

- Delphi/Object Pascal, 1.8%

The Pypl Popularity of Programming Language index gauges language popularity by analyzing how often language tutorials are searched on in Google. The Pypl index top 10 for March 2025:

Anthropic debuts Claude Marketplace to target AI procurement bottlenecks 9 Mar 2026, 11:38 am

Anthropic has launched a new marketplace for tools built on its Claude large language models (LLMs) that analysts say could help streamline procurement hurdles, which often slow the adoption of generative AI for enterprises.

Called Claude Marketplace, the platform currently has a limited set of partners, including Replit, Lovable Labs, GitLab, Snowflake, Harvey AI, and Rogo, offering tools across software development, legal workflows, financial analysis, and enterprise data operations, respectively.

“Most enterprises are not struggling to find capable models. They are struggling to operationalize them inside complex environments that already contain hundreds of applications, strict governance controls, and layered procurement processes,” said Sanchit Vir Gogia, chief analyst at Greyhound Research.

“Every new AI tool typically triggers security reviews, legal vetting, vendor onboarding, procurement approval, integration testing, and ongoing governance oversight. That process alone can delay deployment by months. The marketplace attempts to compress that operational friction,” Gogia added.

The billing for tools in the marketplace, which is charged against an enterprise’s existing committed spend on Claude, is also designed to help streamline procurement by eliminating the need for separate vendor contracts or payment processes.

“Historically, a company would need to negotiate separately with Anthropic and with Harvey or GitLab. Anthropic will manage all invoicing for partner spend, so it’s one contract, one invoice, one renewal conversation. For large enterprises where procurement cycles can take months, this is genuinely valuable,” said Pareekh Jain, founder of Pareekh Consulting.

Strategic lock-in and enterprise proliferation

Beyond simplifying procurement, however, Jain says there’s a deeper strategic play in Anthropic managing partner spend within the marketplace.

“Anthropic earns primarily through API consumption, so every partner application running on Claude generates token revenue. In that sense, the marketplace functions as a distribution engine rather than a toll booth, an approach similar to Amazon Web Services’ early ecosystem expansion, where lowering friction for partners accelerated adoption before deeper monetization,” Jain said.

The analyst added that managing marketplace billing also reflects a broader strategy of strengthening platform lock-in, echoing how Salesforce built its ecosystem around AppExchange and how Microsoft is expanding its footprint with Microsoft Copilot integrations.

“Anthropic is trying to deepen switching costs. Once an enterprise has committed to Anthropic spend and multiple partner tools running through Claude, migrating to another model becomes operationally difficult,” Jain said.

That dynamic, he added, could help Anthropic position itself as “the core AI commitment layer” inside enterprise budgets, increasing the likelihood of Claude becoming the primary line item rather than one of several separate AI tools.

Building a competitive edge

The marketplace may be Anthropic’s first step in creating an edge as competition among AI model makers grows.

“If tools like Harvey gain traction partly because they run on Claude within an existing Anthropic commitment, partners have incentives to stay aligned with Claude even as rival models improve, creating mutual lock-in,” Jain said.

This strategy, Greyhound Research’s Gogia said, will create a behavioral incentive for developers and startups to prioritize Claude integration if they want access to enterprise buyers participating in the marketplace, and over time, that dynamic can expand the partner ecosystem around the platform.

Channel conflict and narrative counterbalance

However, Gogia warned that Anthropic could be heading towards channel conflict.

“Anthropic is simultaneously building its own first-party AI tools while enabling third-party SaaS vendors to extend Claude capabilities through the marketplace,” Gogia said, referring to Claude Cowork and other plugins that triggered a sell-off among several SaaS stocks earlier this year as investors worried that native AI agents could begin encroaching on parts of the traditional software stack.

“The company must balance encouraging ecosystem innovation while ensuring that its own product roadmap does not compete directly with partner offerings,” Gogia added.

Furthermore, the analyst said that the launch of the marketplace is opportune for the company and can be seen as a “narrative counterbalance” to the imbroglio it is currently facing with the US Department of War, which has marked it as a supply chain risk.

“In practical terms, the marketplace demonstrates forward momentum in the enterprise segment. It signals that Anthropic continues to deepen relationships with enterprise software vendors and commercial customers even as the imbroglio unfolds,” Gogia said.

Last week, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei himself, via a blog post, tried to reassure customers that the impasse with the DoW wouldn’t affect them.

How generative UI cut our development time from months to weeks 9 Mar 2026, 10:00 am

When we shipped a new feature last quarter, it would have taken three months to build traditionally. It took two weeks. Not because we cut corners or hired contractors, but I fundamentally changed how we create user interfaces.

The feature was a customer service dashboard that adapts its layout and information density based on the specific issue a representative is handling. A billing dispute shows different data than a technical support case. A high-value customer gets a different view than a standard inquiry. Previously, building this meant months of requirements gathering, design iterations and front-end development for every permutation.

Instead, I defined my team to use generative UI: AI systems that create interface components dynamically based on context and user needs.

What does generative UI mean in reality?

The range of possibilities here is broad. On one end of the spectrum, developers use AI to generate code to build an interface more quickly. On the far end, interfaces are dynamically assembled entirely at runtime.

I lead and implemented an approach that exists somewhere in between. We specify a library of components and allowable layout patterns that define the constraints of our design system. The AI then chooses components from this library, customizes them based on context and lays them out appropriately for each unique user interaction.

The interface never really gets designed — it just gets composed on demand using building blocks we’ve already designed.

Applied to our customer service dashboard, we can feed information about the customer record, type of issue, support rep’s role and experience, and recent history into the system to assemble an interface tailor-made to be most effective for that situation. An expert rep assisting with a complex technical problem will see system logs and advanced troubleshooting tools. A new rep assisting with a basic billing inquiry will see simplified information and workflow guidance.

Both interfaces would look different but are assembled from the common library of components designed by our UI team.

The technical architecture

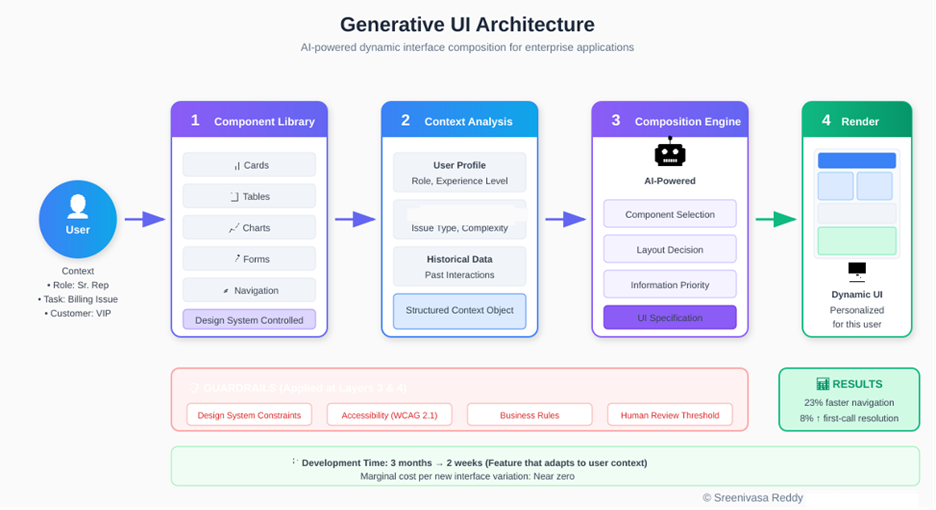

Our generative UI system has four layers, each with clear responsibilities.

Sreenivasa Reddy Hulebeedu Reddy

- The component library layer: It contains all approved UI elements: cards, tables, charts, forms, navigation patterns and layout templates. This follows the principles of design systems. Each component has defined parameters, styling options and behavior specifications. This layer is maintained by our design system team and represents the visual and interaction standards for our applications.

- The context analysis layer: Thisprocesses information about the current user, their task and relevant data. For customer service, this includes customer attributes, issue classification, historical interactions and representative profile. This layer transforms raw data into structured context that informs interface generation.

- The composition engine layer: Hereis where AI enters the picture. Given the available components and the current context, this layer determines what to show, how to arrange it and what level of detail to present. We use a fine-tuned language model that has learned our design patterns and business rules through extensive examples.

- The rendering layer: Ittakes the composition specification and produces the actual interface. This layer handles the technical details of turning abstract component descriptions into rendered UI elements.

How we built it

We built the generative UI system over the course of four months. The first step was building the component library. Our design team took an inventory of every UI pattern deployed across our customer service applications. 27 components in all, from simple data cards to interactive tables. Each component was parameterized based on what data to show, how to react to user input and how to adjust to screen sizes, among other properties. The result was our component library.

The context analysis layer then had to interface with three different backends. Our CRM, which stores information about customers, our ticketing system, which has details about issue classifications, and our workforce management system, which maintains representative profiles. Each of these systems required adapters that would funnel context data into a normalized context object that the composition engine could read.

Finally, for the composition engine, we performed “prompt tuning” on a language model with 2k demonstrations of how our designers mapped context to interface by hand. The model learned relations such as “complex technical issue + senior rep => detailed diagnostic view” without those explicit rules being programmed. Instead of hardcoding thousands of if/then statements, we were able to bake designer knowledge into the model.

The system is deployed onto our cloud architecture, which serves the UI with a latency of less than 200ms, making the generation process invisible to users.

Guardrails that make it enterprise-ready

Generative systems require constraints to be enterprise-ready. We learned this through early experiments where the AI made creative but inappropriate interface decisions that are technically functional but violate brand guidelines or accessibility standards.

Our guardrails operate at multiple levels. Design system constraints ensure every generated interface complies with our visual standards. The AI can only select from approved components and can only configure them within approved parameter ranges. It cannot invent new colors, typography or interaction patterns.

Accessibility requirements are non-negotiable filters. Every generated interface is validated against WCAG guidelines before rendering. Components that would create accessibility violations are automatically excluded from consideration.

Business rule constraints encode domain-specific requirements. Certain data elements must always appear together. Certain actions require specific confirmations. Customer financial information has display requirements regardless of context. These rules are defined by business stakeholders and enforced by the system.

Human review thresholds trigger manual approval for unusual compositions. If the AI proposes an interface significantly different from historical patterns, it’s flagged for designer review before deployment.

Where it works and where it doesn’t

Generative UI isn’t a universal solution. It excels in specific contexts and creates unnecessary complexity in others.

It works well for high-variation workflows where users face different situations requiring different information. Customer service, field operations and case management applications benefit significantly. It also works for personalization at scale, when you need to adapt interfaces for different user roles, experience levels or preferences without building separate versions for each.

It doesn’t make sense for simple, low-variation interfaces where a single well-designed layout serves all users effectively. A settings page or login screen doesn’t need dynamic generation. It’s also the wrong approach for highly regulated forms where the exact layout is mandated by compliance requirements like tax forms, legal documents or medical intake forms, should remain static and auditable.

The investment in building a generative UI system only pays off when interface variation is a genuine problem. If you’re building ten different dashboards for ten different user types, it’s worth considering. If you’re building one dashboard that works for everyone, stick with traditional methods.

Why this matters for enterprise development

Enterprise application development tends to follow a tried-and-true formula. Stakeholders express requirements. Designers mockup solutions. Developers implement interfaces. QA exercises the whole system. Repeat for each new requirement or variant context.

It’s a process that produces results. However, it doesn’t scale well and tends to be slow. Say we want to build a customer service application. Different issue types require different information views. Different customers may see different interfaces. Support reps may see different screens based on their role or channel of interaction. Manually designing and building every combination would take forever (and a lot of money). Instead, we settle, we build flexible but mediocre interfaces that reasonably accommodate every situation.

Generative UI eliminates this compromise. Once you’ve built the system, the cost of adding a new variant of the UI becomes negligible. Rather than picking ten use cases to design perfectly for, we can accommodate hundreds.

In our case, the business results were profound. Service reps spent 23% less time scrolling through screens to find the info they needed. First call resolution increased by 8%. Reps gave higher satisfaction ratings because they felt like the software was molded to their needs instead of forcing them into a one-size-fits-all process.

Organizational implications

Adopting generative UI changes how design and development teams work.

Designers shift from creating specific interfaces to defining component systems and composition rules. This is a different skill set that needs more systematic thinking, more attention to edge cases, more collaboration with AI systems. Some designers find this liberating; others find it frustrating. Plan for change management.

Developers focus more on infrastructure and less on UI implementation. Building and maintaining the generative system requires engineering investment, but once operational, the marginal effort per interface variation drops dramatically. This frees developer capacity for other priorities.

Quality assurance becomes continuous rather than episodic. With dynamic interfaces, you can’t test every possible output. Instead, you validate the components, the composition rules and the guardrails. As Martin Fowler notes about testing strategies, QA teams need new tools and methodologies for this kind of testing.

How to adopt generative UI

My advice to IT leaders evaluating generative UI is to start small with a pilot program to prove value before scaling across your organization. Find a workflow with high variability that has measurable results. Turn on generative UI for that single use case. Measure the impact to user productivity, satisfaction and business outcomes. Leverage those results to secure further investment.

Focus on your component library before enabling dynamic composition. The AI can only create great experiences if it has great building blocks. Focus on design system maturity before you prioritize generative features.

Define your guardrails up front. The guardrails that will make your generative UI solution enterprise-ready are not an afterthought. They’re requirements. Build them in lockstep with your generative features.

The future looks bright

The move from static interfaces to generative interfaces is really just one example of a larger trend we’re starting to see play out across enterprise software: The gradual shift from “static” technology designed for the most-common use cases upfront to dynamic technology that can adapt to the user’s context as they need it.

We’ve already started to see this play out with search, recommendations and content. UI is next.

For forward-looking enterprises that are willing to put in the upfront work to create robust component libraries, establish governance frameworks and build thoughtful AI integrations, Generative UI can enable applications that work for your users, instead of the other way around.

And that’s not just an incremental improvement in efficiency. That’s a whole new way of interacting with enterprise software.

This article is published as part of the Foundry Expert Contributor Network.

Want to join?

Coding for agents 9 Mar 2026, 9:00 am

Large language models (LLMs) and AI agents aren’t important to software engineering because they can write code at superhuman speeds. Without the right guardrails, as I’ve highlighted, that speed simply translates into mass-produced technical debt. No, agentic coding matters because it fundamentally changes what counts as good software engineering.

For years, developers could get away with optimizing for personal taste. If a framework fit your brain, if a workflow felt elegant, if a codebase reflected your particular theory of how software ought to be built, that was often enough. The machine would eventually do what you told it to do. Agents change that equation. They don’t reward the cleverest workflow. They reward the most legible one and, increasingly, the one that is optimized for them. This may seem scary but it’s actually healthy.

Just ask Hamel Husain.

Speaking to machines

It’s not hard to find know-it-all Hacker News developers with strong opinions on exactly what everyone should be using to build. Husain, however, is different. When he blogged about nixing his use of nbdev, he wasn’t walking away from some random side project. He was dumping his project, something he helped build and spent years championing. The reason? It wasn’t AI-friendly. “I was swimming upstream,” he notes, because nbdev’s idiosyncratic approach was “like fighting the AI instead of working with it.” Instead, he says, he wants to work in an environment where AI has “the highest chance of success.” He’s building according to what the machines like, and not necessarily what he prefers. He won’t be alone.

Developers have always liked to imagine tools as a form of self-expression. Sometimes they are. But agents are making tools look a lot more like infrastructure. Husain says Cursor won because it felt familiar, letting developers change habits gradually instead of demanding a new worldview on day one. That sounds a lot like the argument I made in “Why ‘boring’ VS Code keeps winning.” Familiarity used to matter mostly because humans like low-friction tools. Now it matters because models do, too. A repo layout, framework, or language that looks like the training distribution gives the model a better shot at doing useful work. In the agent era, conformity isn’t capitulation. It’s leverage.

GitHub’s latest Octoverse analysis makes the point with data. In August 2025, TypeScript overtook both Python and JavaScript as the most-used language on GitHub. GitHub’s reasoning is that AI compatibility is becoming part of technology choice itself, not just a nice bonus after the choice is made. It also reports that TypeScript grew 66% year over year and explains why: Strongly typed languages give models clearer constraints, which helps them generate more reliable, contextually correct code. As Husain says of his decision to eschew a Python-only path to use TypeScript, “typed languages make AI-generated code more reliable in production.”

That doesn’t mean every team should sprint into a TypeScript rewrite, but it does mean the case for quirky, under-documented, “trust me, it’s elegant” engineering is getting weaker. Agents like explicitness. They like schemas. They like guardrails.

In short, they like boring.

Engineering economics 101

This is the deeper change in software engineering. The agent story isn’t really about code generation. It’s about engineering economics. Once the cost of producing code drops, the bottleneck moves somewhere else. I’ve explained before that typing is never the real constraint in software engineering. Validation and integration are. Agents don’t remove that problem; instead, they make output cheap and verification expensive, which reorders the entire software development life cycle.

The best public evidence for that comes from two very different places. Or, rather, from their seeming contradictions.

The first is a METR study on experienced open source developers. In a randomized trial, developers using early-2025 AI tools took 19% longer to complete issues in repositories they already knew well, all while thinking they’d actually gone faster. Contrast this with OpenAI’s recent “harness engineering” essay, where the company says a small team used Codex to build roughly a million lines of code over five months and merge around 1,500 pull requests. These results seem superficially at odds until you realize that METR’s survey measured naive use of AI, whereas OpenAI’s example shows what happens when a team redesigns software development for agents, rather than simply sprinkling agentic pixie dust on old workflows.

In OpenAI’s experiment, engineers were no longer asked to write code. Instead they were told their primary job was to “design environments, specify intent, and build feedback loops” that allowed agents to do reliable work. Over the course of the pilot, they found that they’d initially underspecified the environment the agents would operate in, but they eventually shifted to a focus on creating systems in which generated code can be trusted.

Of course, this means that AI-driven coding requires just as much human intervention as before. It’s just a different kind of intervention.

This is playing out in the job market even as I type this (and yes, I wrote this post myself). Kenton Varda recently posted: “Worries that software developer jobs are going away are backwards.” He’s directionally right. If agents lower the cost of building software, the likely effect will be more software, not less. As he intimates, we’ll see more niche applications, more internal tools, and more custom systems that previously weren’t worth the effort. Indeed, we’re seeing the software developer job market significantly outpace the overall job market, even as AI allegedly comes to claim those jobs.

It’s not. We still need people to steer while the agents take on more of the execution.

Inspecting the agents

This is where Husain’s focus on evals becomes so important. In his LLM evals FAQ, he says the teams he’s worked with spend 60% to 80% of development time on error analysis and evaluation. He’s also written one of the clearest summaries I’ve seen of how agent-era software development works: Documentation tells the agent what to do, telemetry tells it whether it worked, and evals tell it whether the output is good. Anthropic says much the same thing in its Best Practices for Claude Code, saying the “single highest-leverage thing” you can do is give the model a way to verify its own work with tests, screenshots, or expected outputs.

This also changes what a repository is. It used to be a place where humans stored source code and left a few breadcrumbs for other humans. Increasingly it’s also an operating manual for agents. OpenAI says Codex started with an AGENTS.md file but then learned that one giant agent manual quickly becomes stale and unhelpful. What worked better was treating AGENTS.md as a short map into a structured in-repo knowledge base. That is a very agent-native insight. Build commands, test instructions, architecture notes, design docs, constraints, and non-goals are no longer ancillary documentation. They are part of the executable context for development itself.

More bluntly? Context is now infrastructure.

So many teams are about to discover that their software practices are worse than they thought. Undocumented scripts, magical local setup, flaky tests, tribal-knowledge architecture, vague tickets, inconsistent naming, and “every senior engineer does it a little differently.” Humans just learned to absorb it. Agents expose this silliness immediately. An underspecified environment doesn’t create creativity; it creates garbage. If you drop an agent into a messy codebase and it flails, that’s not necessarily an indictment of the agent. Often it’s a very efficient audit of your engineering discipline. The repo is finally telling the truth about itself.

Which is why I’d now say that my suggestion that AI coding requires developers to become better managers was true, if incomplete. Yes, developers need to become better managers of machines. But more importantly, they need to become better engineers in the old-fashioned sense: better at specifications, boundaries, “golden paths,” etc. The agent era rewards discipline far more than cleverness, and that’s probably overdue.

So no, the big story of coding agents isn’t that they can write code. Plain chatbots could already fake that part. The big story is that they are changing what competent software engineering looks like. Agents reward exactly the things developers have long claimed to value but often avoided in practice: explicitness, consistency, testability, and proof. In the age of agents, boring software engineering doesn’t just scale better, it does most everything—collaboration, debugging, etc.—better.

19 large language models for safety or danger 9 Mar 2026, 9:00 am

Everyone working on artificial intelligence these days fears the worst-case scenario. The precocious LLM will suddenly glide off the rails and start spouting dangerous thoughts. One minute it’s a genius that’s going to take all our jobs, and the next it’s an odd crank spouting hatred, insurrection, or worse.